This post is Part 2 of Belén Maya’s interview. Click here to return to Part 1. Click here for Part 3.

As the conversation continues, it touches on the topics of education, artistic personality, machismo, and more.

The interview was conducted on April 06, 2018, at the Ikea restaurant/café in Jerez De La Frontera, Spain. It is being presented over the course of several posts.

What would you say have been your biggest achievements so far? What are you most proud of?

What would you say have been your biggest achievements so far? What are you most proud of?

I’m proud of how brave I was then, when I did the [Saura] movie. This is the example that I always talk about, the dress. When I got there the first thing they told me, not Saura, but the rest of the crew, they told me, “are you going to dance flamenco in that? You cannot dance flamenco in that dress. This is not a flamenco dress, it’s green and it has no ruffles, and you don’t have a mantón and you don’t have a flower. What kind of dancer are you?” That’s the first thing they told me when I got to the set. Carlos saw me and he said, “oh, you’re perfect.” That’s what he wanted. But there was always this backlash in my career, there was this, “what are you doing? Nobody understands what you are doing. You don’t look flamenca, or you don’t sound flamenca, or you don’t move flamenca, or this is too complicated.” My show Bailes Alegres, for example, three shows ago, it was based on a movie of Ingmar Bergman called Persona and I had an artistic director, a choreography director, a costume designer. This whole crew that was working to adapt Persona, the movie, to flamenco. What they said in Jerez was, “we didn’t understand what it was all about, why don’t you just dance por Soleá?” I’m proud of always pushing the limits. Some people come to me and tell me, “thank you because I loved green and I loved your dress and you gave me permission to wear that and be flamenco.”

A friend of mine said you told her that after the movie, some of your friends wouldn’t talk to you.

Yeah (laughing). They were like, “if you don’t do this, then you’re not in the club.” And I was like, who cares? I got this opportunity to be who I am, completely, 100%. Carlos [Saura], I promise, he saw me and he said, “you’re perfect.” He saw the choreography and it was just one minute and he said, “this is just what I wanted, you’re perfect.” And I was like, “I’m okay, I’m okay!”

Do you feel recognized for the things you’ve contributed to the world of dance?

Yes, I feel recognized, but not by the institutions in Spain. For example, not by the Junta de Andalucía, the Bienal [de Sevilla], or Festival de Jerez, not by them. They don’t like me, they don’t support me, and they don’t support my work. But, I feel recognized, [for example], by this woman in Germany that came after the show crying and told me, “thank you because I can do flamenco because you’re alive. I’m not from Jerez and I’m not Gypsy; I’m blonde and I don’t speak Spanish. But I feel I have permission.” To me, that’s like winning a prize.

What do you think is different about how young people start careers in flamenco now compared to when you were starting out?

When I was young you had to know how to dance classical Spanish dance, Jota, Gallego, all the original folk dances. You had to play castanets a little bit, and then dance flamenco. You had to be a complete dancer. Right now, if you want to dance flamenco you go directly to flamenco and skip all the rest. The looks are important, having your website, Facebook, all those things, and looking, not pretty, but fashionable. [You need] to make a good video, have good pictures, have a good image. That’s really important now, and to have your group, a small company, and try to make it big. For example, the young dancers right now send their projects to the Bienal and Festival de Jerez. Even the small companies send [their projects] and try to get in because that’s the big showcase. All the programmers and directors from France and the Unites States go to Jerez and the Bienal and they hire and program everybody. You don’t go from here to here like I did (gesturing), starting in the tablao, then the small company and then you get a little bigger. Now you try to jump directly to these big venues. You spend much more money. You invest a lot in your company, in your costumes; you invest a lot to try to make that jump. Because then if you get there, the big programmers will see you and will hire you from there. So, it’s completely the opposite [of my experience].

Do you think the younger artists are less prepared because of that?

No, I think they’re very well prepared. They have a lot of technique, much more technique than when I started. Technically they are perfect. What I think is that they don’t have enough experience. They haven’t touched tablao enough or big companies enough or touring enough. They want to be too [unique] too early and don’t build their personality little by little. They want to be Rocio Molina when they are 20 and that’s impossible. Rocio Molina, there’s only one, and she was Rocio Molina when she was five and ten. Israel Galván, the same, he was a genius when he was 14, 15, 20, 22. But they’re geniuses.

Yeah, they’re special.

They’re special. So, these [young] people want to be very [unique] and you can’t be when you’re only 18 years old. I think they’re trying to go too fast, a lot of them.

You’re going to the United States right now to teach; do you teach a lot here [in Spain] too?

Yeah.

What have you seen in terms of the way flamenco is learned and taught? How have you seen that change over time?

When I started at Amor de Dios… well, Amor de Dios was the old school where my parents studied and taught. All the big teachers were there and it was like a church. You entered like this (gesturing reverently). These teachers, like Manolete or Güito, for example, they wouldn’t teach you a whole choreography. Right now, students want you to teach them, from beginning to end, everything, all the difficult steps. These old teachers, you learned a lot from just watching them speak, their attitude, and the way they dressed. They were completely different individual personalities, from Güito to Manolete, Manolete to my father, my father to Paco Romero. Now we’re all alike. We look similar, for example, Mercedes Ruiz, Patricia [Guerrero], these young women don’t look so different. I don’t know why, but they look similar. In those times, they all were so completely different. And [their personalities] were not based in technique. The teachers were not based in technique or steps. It was based in how you lived flamenco, in what you understood. It was more artistic. For example, with the singing, they would explain what you heard in one Soleá that was different from another Soleá. They would tell you a lot about their youth and how they started. You got a lot of teacher-student communication and experience. Right now, there is nothing. You cannot speak in a class. If you speak, [the students] don’t want you [as a teacher], because they want steps. There’s no oral transmission, which I think is so important in flamenco.

I was talking to one of the other people I interviewed about the old, traditional Casas Antiguos de Vecinos (Traditional Houses of Neighbors), and how they cultivated an environment for the art form’s oral transmission and it was very natural. But, there are so few of those left that preserving the oral transmission is really hard and it doesn’t happen the same way anymore. Places like Amor de Dios started in the 70s and the Fundación [Cristina Heeren] started in the 90s, but even so, the concept of an official, formal school for flamenco is pretty new. How do you think that’s changing the nature of flamenco?

Flamenco has become a commodity. It has become a product. We all know it because it’s making a lot of money. There’s a whole infrastructure. There’s an industry of flamenco. Junta de Andalucía knows it, Festival de Jerez and Bienal know it, and they make a lot of money from it. If it’s a product, it has to have an image and has to be understood. It has to be made easy for foreigners and people who are not in the circle. There are two different things [going on]. One is commercializing the code of flamenco to sell it. The other thing, which is what I believe in, is to explain the code of flamenco so that foreigners and people that love it can grow into it, can know more, and can dance or sing or play guitar better and be part of it. There’s a secrecy [found] in the past that I didn’t like, that [flamenco] belonged to the schools, to the Casas de Vecinos, or to the families. If you were not Roma, were not Spanish, or you didn’t belong to the Casa or to the group, you wouldn’t learn the code. You would never understand the structure or how it was played. Why do you go out and start [dancing]? Why does the singer start singing? A llamada (call), a cierre (close), all this, I like to explain this coding because I don’t believe flamenco needs to be secret. I don’t start from a position of making flamenco accessible because it’s a product. I want it to be accessible to everybody because it’s a transformative art form. It changes your life completely. It changes the way you see yourself. For example, women in Japan or the United States, they always tell me same thing. They feel empowered as women because of flamenco. It makes you believe in yourself. It makes you stronger. It makes you braver, more able to face life, [gives you] different tools, power, and [makes you] grounded. You have to be grounded to do footwork. You cannot be like new-age peace and love, no! You have to be here (gesturing inward). All these things transform your life and transform your body. That’s why I want to make it accessible, not because it’s a product. I believe in the oral transmission, but not in an oral transmission that makes you good or bad, that you must be in or out, but an open oral transmission. You don’t have to be inside the family, or inside the house, or inside the school, or inside the race, Roma or not-Roma, no.

What has been your experience regarding machismo in flamenco?

(Takes deep breath.) If you look at the history and tradition of flamenco and where it comes from, it’s all based in machismo. Everything is machista, [just] listen to the lyrics. If you work in a company, the musicians are all men. The entire backdrop is men, they’re behind everything. You as a performer, the director of a company, as a choreographer, and as a female dancer, have to constantly face a lack of support as a female boss of all these men. It’s really difficult. There’s also the stereotype of the bailaora (female dancer) that has to look a certain way and move a certain way, the seduction, and the objectification, [all this] inside in art form that is already very limited. You’re limited by tradition and you’re more limited because you’re a woman. Your space is really small. What I try to do when I teach is give tools to free all these women. You don’t have to look Roma, you don’t have to look Spanish, you don’t have to have this [curvy] shape and be beautiful and dark and whatever. You don’t have to look like anything. You can be Japanese, German, Swedish, French, it doesn’t matter. You just have to feel certain things and find those energies and emotions in your life and in your body and that’s all.

Do you think that’s the main reason or are there other reasons why there are so few female guitarists?

Sure. I don’t know, but I imagine it must be so, so difficult to enter a world of only men. All the guitarists are men. It must be horrible.

I’ve only seen a few women, there was one who played in New Mexico with Olga Pericet’s company when I was there.

Ah yeah, Antonia [Jimenez].

I’ve seen a couple others, but not many.

They say there’s also this problem of strength in the wrist and fingers. They, male guitarists, say women don’t have enough strength to play the guitar, but I’m sure that’s bullshit.

There are a number of ways to play the guitar.

Of course!

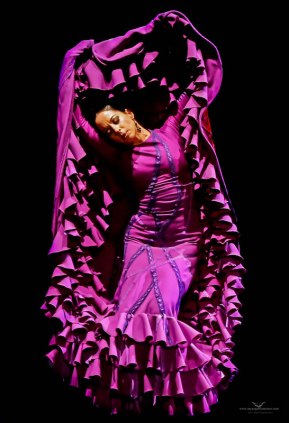

This post is Part 2 of Belén Maya’s interview. Click here to return to Part 1. Click here for Part 3. Media courtesy of Belén Maya Compañía.

For additional excerpts of this interview and others, click Follow at bottom left to follow the blog and receive email updates.

If you would like to support Palabras Flamencas, please click the Donate button below or click here to purchase the author’s album, Punto Lejano. Thank you.

De Las guitarristas femininas, no olvidan Maria Temjo. Aun de EEUU, baila, canta y es una guitarrita maravillosa. ¡Hasta professora de musica!

LikeLike

Gracias por el buen recordatorio. Le pongo en mi lista y a lo mejor pudiera hacerle una entrevista en el futuro.

LikeLike